The Ladies of Kenwood House

Three Women linked to the (free) English Heritage gem in North London

Have you visited Kenwood House?

On the edge of Hampstead Heath sits an elegant country house, reimagined as a neoclassical villa during the late 18th century for William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield.

Kenwood House has been a family home and a weekend retreat since the 17th century but from the 1920s it has been open – for free – to the public who can enjoy the world class interiors and art collection.

The story of Kenwood is most often told through the Earls who owned it but in this post I wanted to take a look at three women who have connections to Kenwood House.

But first, below is the latest availability for public walks August.

(Click on the name to book)

August Walking Tour Availability

Sunday 3 August, 11am - Bankside Behaving Badly

Sunday 3 August, 2pm - Hidden Wonders of Waterloo

Saturday 23 August, 11am - City: Power and Sacrifice

Saturday 23 August, 2pm - The Spirit of Spitalfields

Sunday 24 August, 2pm - Sordid Soho - only 1 spot left

The Great-Niece

The 1st Earl Mansfield and his wife Elizabeth Finch didn’t have children of their own and in the 1760s two young girls from very different circumstances arrived at Kenwood House.

They would grow up together here, in a new family home.

Lady Elizabeth Murray was the daughter of Lord Mansfield’s nephew and heir but her mother, Henrietta, had died in 1766.

Dido Elizabeth Belle was the illegitimate daughter of Sir John Lindsay, a British naval officer and Maria Bell, an African woman.

In the decadent surroundings of Kenwood House and its extensive gardens the two young girls seemingly had an idyllic life. But of course they were living against a backdrop of the state-sponsored transatlantic slave trade as well as the unstable legal status of black people in 18th century Britain.

Dido was born in London on 29 June 1761 around 1760 and baptised in 1766 at St George’s Bloomsbury, close to the Bloomsbury townhouse (now demolished) owned Lord Mansfield.

It’s tricky to understand Dido’s status and life within the walls of Kenwood House but it seems that she enjoyed a similar upbringing to Elizabeth Murray who was only a few months older.

They played together and were both educated by private tutors who came to the house. It was through this tutoring that Dido would learn French which would be useful for her life after Kenwood.

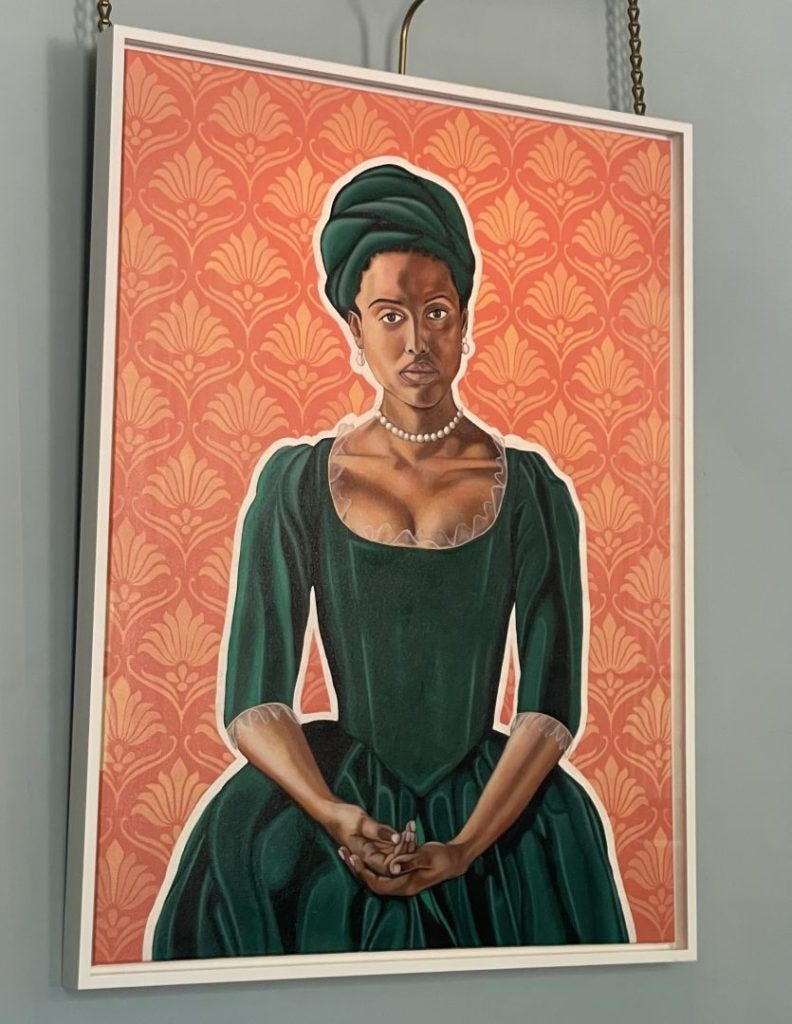

A replica of a double portrait of the pair hangs in Kenwood House and is a much more dynamic representation of a woman of colour than is usually seen in 17th and 18th century British portraiture.

To illustrate the difference, here are two examples of portraits of aristocrats painted alongside black servants.

The painting of the Duchess of Portsmouth, mistress of King Charles II, hangs in the National Portrait Gallery. The unnamed servant looks up lovingly at the Duchess and holds exotic items. Sadly she’s not depicted as an individual but more as a prop to showcase the taste and fashionable lifestyle of the sitter.

Similarly in Ham House you can find this portrait from c.1740 showing Lady Grace Carteret with a child and black servant. Both children gaze lovingly at Lady Grace but the young boy, holding a cockatoo is painted at a lower level than other, white sitters.

In contrast the portrait of Dido and Elizabeth show them both gazing out at the viewer. Yes, Dido is standing slightly behind Elizabeth and her outfit is heavily exoticised with a feathered turban I think you can clearly see she has more autonomy and personality.

Most of the insights we can glean of Belle’s life at Kenwood is from the letters from visiting guests, each with their own views and prejudice. Thomas Hutchinson (an American living in London who came for dinner in August 1779) says that Dido “came in after dinner and sat with the ladies and after coffee, walked with the company in the gardens, one of the young ladies having her arm within the other.”

We also know that Lord Mansfield left a considerable amount of money to Dido in his will. Not as much as he left Elizabeth Murray but this was the normal contrast for an illegitimate versus legitimate child. Interestingly he also explicitly states that “I confirm to Dido Elizabeth Belle her freedom”.

Mansfield was chief justice for the Court of the King’s Bench for 32 years and during that time he presided over two important cases concerning the status of black servants in England (Somerset vs Stewart, 1772) and slavery (Zong Massacre, 1783). His rulings didn’t abolish slavery, that would only come much later in 1807 (for the Slave Trade) and then 1833 (for slavery itself) but his decisions helped cement a legal basis for the path to abolition. Personally I find it hard to believe that having Dido at home didn’t sway his decisions.

When Lord Mansfield died in 1793 Dido was 32. She had spent most of her 20s caring for the old earl and now with her future uncertain she married a man called John Louis Daviniere, a French-born Gentleman’s Steward at St George’s Hanover Square. (Told you those French lessons would be helpful!)

The newlyweds moved into 14 Ranelagh Street North which can be seen on the R. Horwood 1799 map of London and is a stone’s throw from Buckingham Palace, on the edge of Belgravia.

It was a 3 bedroom terraced house and the family lived comfortably with a cook and housemaid. Dido had 3 sons, twins John and Charles in 1795 and William Thomas in 1800. Only Charles and William Thomas survived into adulthood.

Dido died in 1804, aged just 43, and was buried in St George’s Church in Tyburn which was sadly demolished in the 1960s.

For more information about Dido Elizabeth Belle there are several in depth blogs by Sarah Murden and Etienne Daly on the All Things Georgian website.

The Countess

Frederica Markham was born in 1774, daughter of the Archbishop of York. In 1797, aged 23 she married David William Murray, 3rd Earl of Mansfield. David had inherited the title and Kenwood House the year before and so she became the Countess of Mansfield.

As an 18th century wife Frederica had no legal status of her own so her contribution to the house and their family life has to be gleaned through scant letters, records and documentation.

This was the problem faced by Cathy Power who curated an exhibition about the ‘Ladies of Kenwood’ back in 2018. She was able to wade through archival material to try to unearth Frederica’s contribution.

One statistic she found was during the late 18th century under Frederica, the number of female servants doubled from 10 female staff to 20 (they also had a butler, steward, four footmen and a cook who were all male).

The amount of help was no doubt appreciated by Frederica who would have 9 children over 16 years.

We also know that between 1813-1816 Frederica made decisions about the redecoration of Kenwood, updating the rooms into the fashionable Regency style.

In a letter from the architect, William Atkinson, he asks about a choice between marble or Wedgwood bowls but the Earl says he’ll wait to decide until he’s confirmed with his wife.

Similarly the gardener in a letter to the Earl says he’s discussed changes to the flower garden with Frederica.

The Countess lived to 86, only dying in 1860 so I found it frustrating to only know small details about her life.

The ‘Dollar Princess’

Marguerite Leiter was born in 1879 but she was better known by everyone as Daisy.

She was born into a wealthy Chicago family, beautiful, witty, clever and charming. Daisy met her future husband Henry Howard on a trip to India while visiting her sisters and they were married in 1904, making her the Countess of Suffolk.

Between 1870 and 1914 over 100 American women married into the British peerage which prompted a panicked media response claiming the relationships were nothing more than “cash for coronets” and the women themselves were known by the reductive nickname “Dollar Princesses”.

Although some of the 102 marriages between wealthy American women and British aristocrats were unhappy, many were love matches and the wives would contribute immensely to British life through politics, charity, art and philanthropy.

Daisy lived in Charlton Park in Wiltshire, a Jacobean mansion which still stands today.

As well as promoting local businesses, during the First World War she converted the Charlton park Picture Gallery into a hospital and made room for Belgian refugees to camp on the estate. It was also during the First World War that her husband died, the oldest of her three sons was only 11.

In the 1920s and now a young widow Daisy seems to revel in adventure. She loved horse-riding – breaking her leg in 1922 and a few ribs in 1924 – but also zoom around in motor cars and even flying her helicopter and small planes.

Her oldest son Jack, the 20th Earl of Suffolk was a bomb disposal expert and served during the Second World War. In 1940 he managed to rescue a team of French nuclear scientists and their stockpile of heavy water into Britain. Tragically, a year later in 1941 he was killed whilst trying to defuse a bomb.

Daisy’s connection to Kenwood comes in the form of philanthropy. In 1974 she gifted the Suffolk Collection, paintings collected over 400 years by the earls of Suffolk and Berkshire.

Today some of the most important work – a group of early 17th century portraits of the Howard family by William Larkin – can be admired on the first floor of Kenwood House.

Daisy died at the age of 89 but her striking portrait by John Singer Sargent from 1898 usually hangs over the stairs in Kenwood. Painted when she 19, her confidence and charm radiate from the canvas.

Visit Kenwood House

Kenwood House stayed in the Murray family until the 6th Earl Mansfield sold the house and part of the gardens to Edward Guinness, 1st Earl of Iveagh in 1925. In 1927 when Guinness died, he gifted Kenwood and his art collection to the nation and by the end of the 1920s Kenwood was open to the public and managed by the London County Council.

It’s thanks to his bequest that today that the public can enjoy Kenwood House and its grounds, today managed by English Heritage.

Until 5 October 2025 you can enjoy a temporary exhibition at Kenwood, “Heiress: Sargents’s Dollar Princesses”. Find out more here. Entrance to the exhibition is ticketed but entry to Kenwood House is free, you can view opening hours on their website here.

Nice to be reminded of Dido Elizabeth Belle.

This is a charming blog, Katie. In fact many of the ladies at the current Singer Sargent exhibition at Kenwood are also mentioned in the current Cartier exhibition at the V & A. There is another exhibition, just opened (which I haven't seen yet) at Mapperton House in Dorset on a similar theme called 'Gilded Age - American Heiresses at Mapperton' which is on until 30 September. I hope to see that one, too.